Why would you have a hospital on a ship? And if you have one, why not two?…

COVID’s Impact on Students: Part 1 The Research

Lower Grades Levels, Low-Income Students Could See Steepest Academic Decline

The Rees-Jones Foundation values equitable academic and enrichment opportunities for children and youth, and supports organizations who endeavor to provide such formative experiences to those in the community who would otherwise not have access. When the pandemic reached North Texas, The Foundation sought opportunities that ensured these students would continue to have uninterrupted access to high-quality education.

According to the most recent US Census data from 2018, in Dallas 27 percent of households do not have access to high speed internet. A study conducted by the Local Educational Agency found that 30 percent (~1.6 million) of Texas students do not have a dedicated or adequate learning device, and up to 1.9 million Texas students lack broadband access.

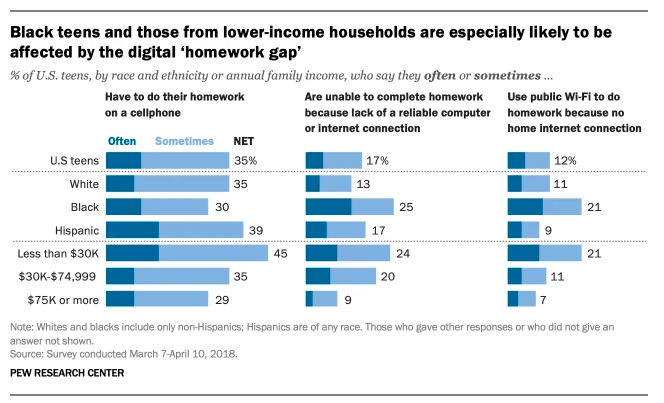

This lack of access to basic technology meant many students were unable to continue learning as most schools pivoted to online instruction. This exposed the “homework gap”, which refers to school-age children that lack the connectivity they need to complete schoolwork at home, and is most prevalent, among black (22 percent of DISD students), Hispanic (70 percent of DISD students) and lower-income households (86 percent of DISD students[1]).

The homework gap isn’t new or unique to Dallas or even Texas. In March of 2020 Pew Research stated that some 15 percent of US households with school-age children do not have high-speed internet at home, and roughly one-third (35 percent) of households with children ages 6-17 and an annual income below $30,000 do not have high-speed internet at home. It would be difficult, if not impossible, for these students to access their live, online classrooms or even retrieve homework assignments distributed through email or online platform. In short, these students were being left behind.

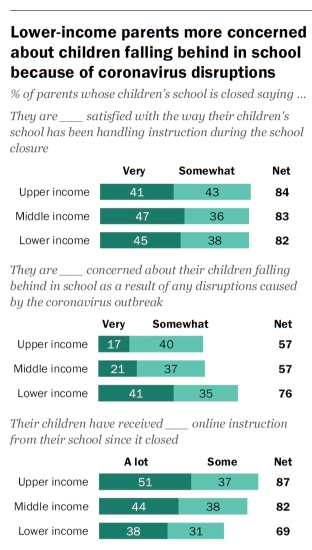

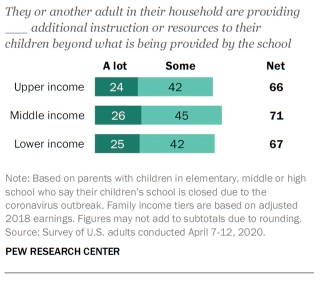

Note: Based on parents with children in elementary, middle or high school who say their children’s school is closed due to the coronavirus outbreak. Family income tiers are based on adjusted 2018 earnings. Figures may not add to subtotals due to rounding. Source: Survey of U.S. adults conducted April 7-12, 2020 (Graphic provided by Pew Research Center).

Another study by Pew Research conducted in April found that about two-thirds of parents with children in K-12 schools were concerned their children were falling behind in light of COVID-related school closures.

The Pew study further extrapolated parent responses into three household income tiers: Households with annual incomes less than $40,100 were placed in the low-income tier, households with annual incomes between $40,100 and $120,400 were deemed middle income, and lastly households with annual incomes greater than $120,400 were considered upper income.

The study revealed that 41 percent of parents in the low-income tier are very concerned about their children falling behind in school as a result of any disruptions caused by the coronavirus outbreak, and 29 percent reported that their children’s school has provided not much or no instruction since in-person schooling ceased.

The level of concern by parents fell by half in the next income bracket with 21 percent of parents in the middle-income tier stating they are very concerned about their children falling behind.

The trend held steady for parents in the upper-income tier with 17 percent expressing that they are very concerned about their children falling behind. This tier also reported higher levels of instruction provided by the school with only 13 percent stating that their children’s school has provided not much or no instruction – half of what parents in low-income households reported.

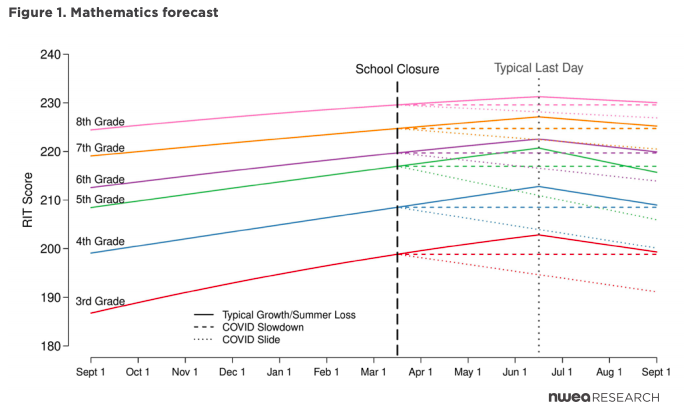

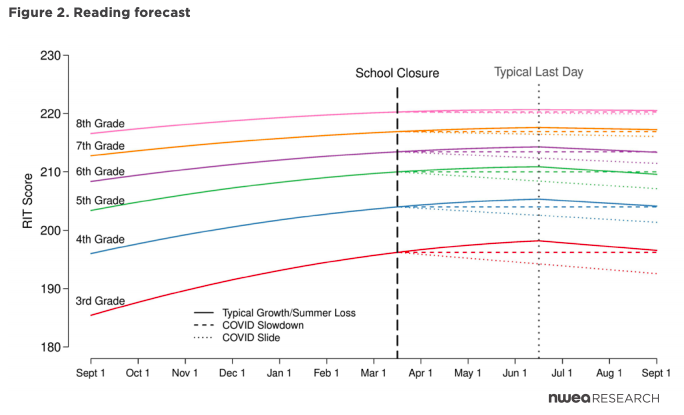

Just how much students fell behind due to learning strains brought about by COVID is still unclear, however, there is existing data that shows how much knowledge students typically lose during the summer months, which is referred to as “summer learning loss”. Using the summer learning loss data, researchers at NWEA, a research-based non-profit organization that creates academic assessments for students in pre-K through grade 12, were able to forecast how COVID might impact academic performance and retention.

To understand these forecasts, it’s important to grasp how much learning loss occurs in a traditional school year for students who do not participate in enrichment programs over the summer. In a typical school year with a standard summer break, NWEA research has established three major trends: Achievement typically slows or declines over the summer months; declines tend to be steeper for math than for reading; and the extent (proportionally) of loss increases in the upper grades.

Using the traditional summer learning loss data, NWEA was able to forecast how much academic loss in math and reading could be expected as a result of extended time out of the traditional classroom setting.

Figures 1 and 2 show how the observed typical average growth trajectory by grade for students who completed a standard-length school year compares to projections under two scenarios for the closures: COVID-19 slide, in which students showed patterns of academic setbacks typical of summers throughout an extended closure; and COVID-19 slowdown, in which students maintained the same level of academic achievement they had when schools were closed (modeled as March 15 with summer resuming in fall).

The solid colored lines each represent the academic learning gains and losses for each grade level in a traditional classroom setting through the school year. Students make academic gains in both reading and math during the school year with some academic loss occurring during the summer. This data was gathered from the MAP Growth assessments of over five million students across the nation, and served as the baseline for the COVID learning loss models.

Each grade level also includes dashed and dotted lines, which each represent academic gains or losses depending on the scenario modeled by NWEA.

The dashed line models academic gains and losses in the COVID slowdown scenario, in which students maintained the same level of academic achievement they had when schools were closed, i.e. students did not gain or lose knowledge but rather maintained their existing knowledge. In this scenario, students would be expected to enter the new school year with the same amount of knowledge they possessed when in-person school ceased on March 15. It should be noted that although these students did not experience summer learning loss, they also did not learn or retain any new material as of March 15.

The dotted line models academic gains and losses in the COVID slide scenario, in which students showed patterns of academic setbacks typical of summers throughout an extended closure, i.e. students begin summer learning loss three months earlier than they do in a traditional school year. This scenario predicts significant academic shortfalls when students begin the new school year in September. For instance, the COVID slide scenario predicts that third graders’ math skills could regress as far back as winter break of the prior school year (2019-20).

According to the study, “Preliminary COVID slide estimates suggest students will return in fall 2020 with roughly 70 percent of the learning gains in reading relative to a typical school year. However, in mathematics, students are likely to show much smaller learning gains and, in some grades, nearly a full year behind what we would observe in normal conditions.”

The major take-away: Missing school for prolonged periods will likely have major impacts on student achievement.

But the NWEA reporting doesn’t explicitly consider learning inequities experienced by students from different socio-economic backgrounds. Based on the findings from the aforementioned Pew studies, students from low-income households had fewer academic opportunities provided by their schools, and statistically, had lower levels of access to internet.

But the NWEA reporting doesn’t explicitly consider learning inequities experienced by students from different socio-economic backgrounds. Based on the findings from the aforementioned Pew studies, students from low-income households had fewer academic opportunities provided by their schools, and statistically, had lower levels of access to internet.

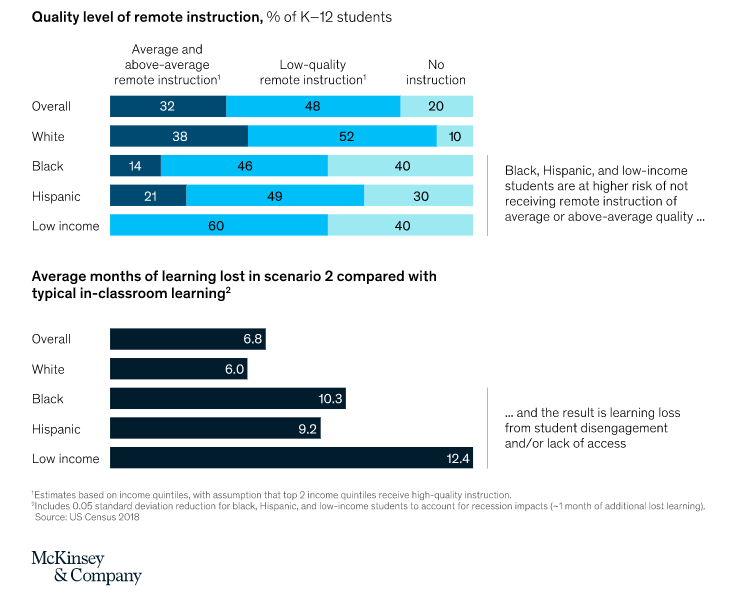

A report by McKinsey & Company that studied the achievement gaps among students prior to COVID-19, showed that “the average black or Hispanic student remains roughly two years behind the average white one, and low-income students continue to be underrepresented among top performers”. McKinsey therefore estimates that COVID-19 could exacerbate the existing achievement gaps by 15 to 20 percent if students do not return to in-person learning by January of 2021.

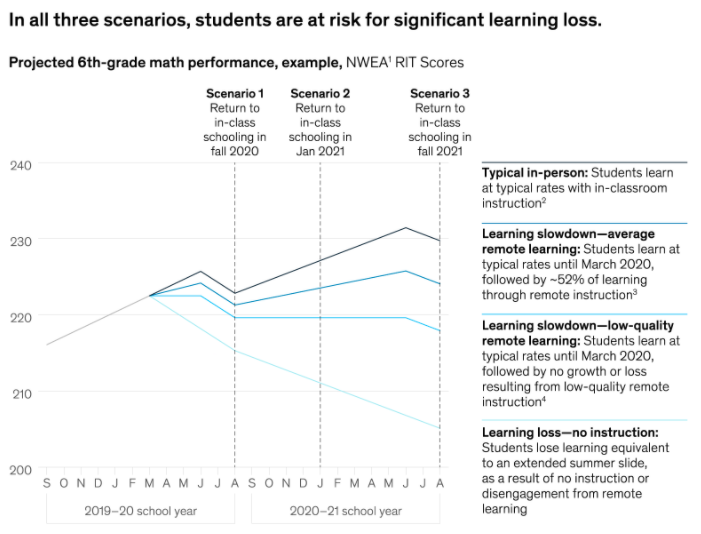

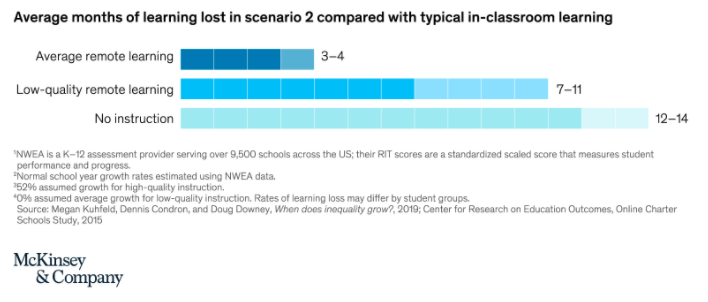

Using data provided by NWEA, McKinsey modeled potential learning losses and gains based on the quality of remote learning that students might receive, i.e. average quality, low quality and no remote learning. McKinsey estimates that “students who remain enrolled could lose three to four months of learning if they receive average remote instruction, seven to 11 months [of learning] with lower-quality remote instruction, and 12 to 14 months [of learning] if they do not receive any instruction at all” assuming that all students return to in-person schooling in January of 2021.

McKinsey concluded that learning loss will likely be greatest among low-income, black and Hispanic students stating, “Lower-income students are less likely to have access to high-quality remote learning or to a conducive learning environment, such as a quiet space with minimal distractions, devices they do not need to share, high-speed internet, and parental academic supervision.”

McKinsey projects the average learning loss for students regardless of socio-economic situation to be seven months, however, projections show that black students may fall behind by 10.3 months, Hispanic students by 9.2 months, and low-income students by more than a year.

Further, based on drop-out rate trends seen following natural disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Hurricane Maria in 2017, where 14 to 20 percent of students never returned to school, McKinsey estimates that an additional 2 to 9 percent of high school students could drop-out as a result of COVID-19.

To prevent these estimates becoming reality, several schools in North Texas have integrated creative solutions based on statistics and their own experiences with virtual learning during Q4. The schools’ main goal is to empower students to continue learning by improving students’ experiences, access, and engagement this school year.

A follow-up to this blog post will focus on the creative solutions that two schools in North Texas have implemented to better serve students and their families – many of whom are still in crisis mode due to the pandemic.

Sneak Peak – KIPP Texas Public Schools

Some high school students at KIPP informed teachers that they were unable to attend live virtual classes during the day because they had to work to help support their families. KIPP decided to record and post the live classroom lessons, so that students who work during the appointed class time could watch as their schedule allowed. This change in programming led to higher engagement among high school students, and has led to administrative staff considering staggered lesson times to better fit their students’ needs.

[1] Economically disadvantaged is defined as a student that qualifies for free or reduced-price lunch or other public assistance. This data, including the race demographics, was provided by TEA and gathered by the Texas Tribune.

Share this post:

Category: Original Content

Power of Place-Based Investments Can Lead to Better Outcomes for Children By Trey Hill, Senior Program Officer…

Why Home Mentoring is Key to Child Abuse Prevention By Ona Foster, CEO of Family Compass [In…