Why would you have a hospital on a ship? And if you have one, why not two?…

By CJ Stevenson, Program Officer

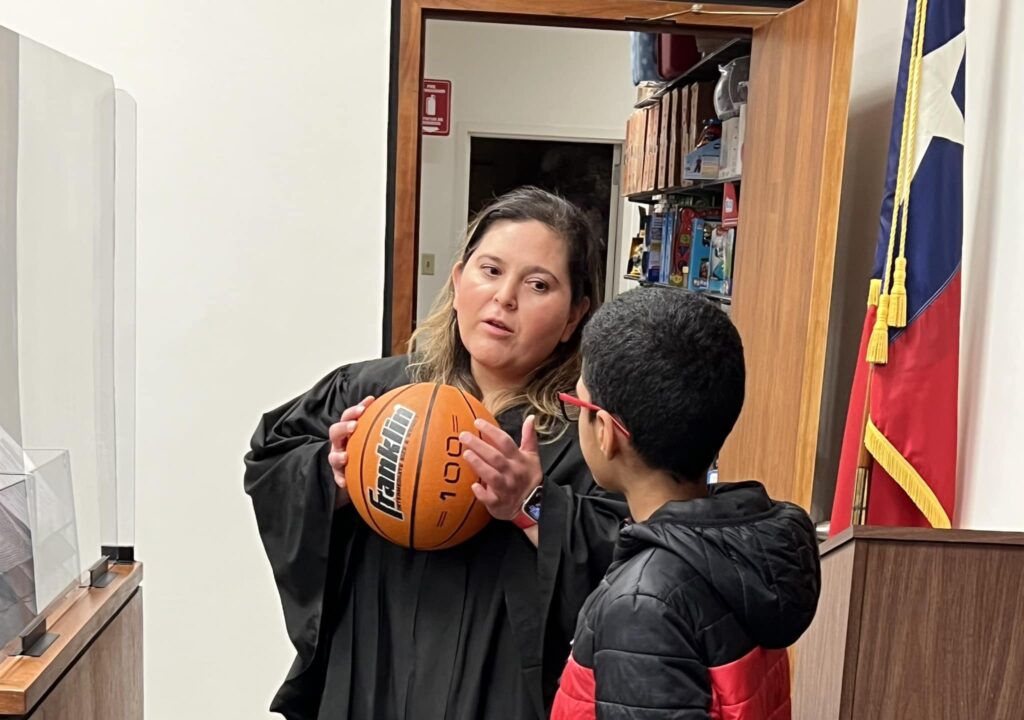

There is a judge who holds court on the fourth floor of the George L. Allen Sr. Courts Building in the West End of Dallas. This is a special court. You won’t appear in front of Judge Delia Gonzales for a speeding ticket or similar offense. Those that enter her court room are seeking permanency amid a life in perceived crisis and chaos. Sibling groups and youth who have found themselves wading through the child welfare system in Dallas County having bounced around foster homes and other temporary shelter for a number of years with no place to call home.

The Dallas County Child Protection and Permanency Court (DCCPPC) was established in 2019 with a mission to ensure all referred children age birth to 18 under Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) conservatorship are heard and find a permanent forever home with positive results. Referrals are very specific to those children who have faced abuse and neglect, abandonment from parents, and/or a host of other qualifying reasons that qualify them for this specialty court’s docket.

The Dallas Permanency Court is only the second court of this type in the nation, and is modeled after a similar court in Houston that specializes in finding permanency for children and youth in the long-term care of DFPS. The Permanency Court was established because of the sheer volume of children in the system, which meant that it was taking four to five years for children and youth to exit the system into a permanent home. Judge Gonzales, who presides over the Dallas Permanency Court, identifies barriers to children’s stability and brings an individualized approach to every child and family.

Without Judge Gonzales and this specialty court, children in permanent state conservatorship would not receive the same level of attention and care due to the volume of child abuse and neglect cases.

Family courts are spaces that specifically adjudicate in matters involving children and families, specifically custody disputes, parental rights, abuse and neglect, child welfare. Family courts are specialized settings comparatively with other courts in the judicial system. Each judge has his or her own personality and runs his or her court in a unique manner, but they all conform to the same pattern of proceedings. . Everyone – attorneys, CPS case workers, CASAs, family members and others – cram into a tiny holding space within the courtroom. There is a strange and silent chaos with prosecutors and guardian ad litems silently slipping between court rooms, motioning to clients to chat outside, the swinging doors of the courtroom constantly admitting and excusing groups of 10 at a time.

Despite it being family court with children’s livelihoods being the topic of discussion, children and youth are rarely in attendance. The courtroom is full of adults – oftentimes unrelated to the child – who are charged with making decisions that impact the child in the most intimate way: who and how they will be cared for.

This permanency court under Judge Gonzales operates differently. It enlists a special judge – the same judge – with a big smile who is able to take the time required to get to know the children entrusted in the state’s care. A constant in a world that is filled with CPS turn-over, numerous foster families, and untold trauma.

Judge Delia Gonzales, who spent 15 years as a guardian ad litem before her judgeship, runs her courtroom in an almost unheard of manner. She organizes her docket in 30-minute blocks allowing her to allocate her entire self to the children in front of her. No one is permitted into the courtroom until their case is called, which allows for a more pleasant experience for all and an unheard of level of privacy for the families involved.

A friendly face greets all case party members in a bright waiting room that packs snacks, toys, and an area similar to a rainbow room where youth and families can access clothing, toiletries and other essential items. When it’s time, Judge Gonzales welcomes the group into her teddy bear filled courtroom. She keeps the mood light, inquires with the children how they’re doing, what they learned in school, and other small talk that coaxes out personalities of even the shyest of children or guarded teens. For the adolescents, she asks pointed questions about behavior in school, grades, friends and the like. Judge Gonzales isn’t nosey, her inquisitiveness comes from a place of deep care and a desire to walk alongside the teens that stand in front of her to help them sort out their lives. She views herself as their advocate, a job she can only do if the teenager is willing be to vulnerable – another reason she keeps the court audience as minimal as possible.

Once Judge Gonzales is satisfied, she asks the children or teens to return to the waiting room while she speaks with the adults.

Judge Gonzales then wastes no time getting down to business. All parties are sworn in, CPS presents their report, followed by CASA and then the attorneys. It moves like a well-oiled machine. Judge Gonzales speaks directly to the parents or caregivers. There is conversation. In one case an aunt and uncle were fostering four children. The grandmother residing in Mexico was very ill and the family wanted to visit her in the coming month. But the children needed passports. With the state having conservatorship over the children, there was discussion as to how the children would obtain passports. Judge Gonzales listened patiently before directing CPS to apply for the passports. Its challenges like these that Judge Gonzales helps to solve – challenges that would have taken months to figure out in a typical court setting.

On another day in court, dubbed “PAL Court”, Judge Gonzales sees older youth who are about to or have aged out of care. Those who have aged out of care, have opted into extended foster care, which is available until the youth turns 21 if the youth attends school or works full time among other requirements.

One of the first cases involves siblings – Derry*, Amanda*, and Ariana*. All three are in extended foster care. Derry is the brother. Derry has been living in supervised independent living for some time, is enrolled at Tarrant County College, but was just put on academic probation. His roommate says he hasn’t been home in weeks. The sibling’s grandfather passed recently, so Derry was staying with his grandmother to help out. However, he’s in jeopardy of losing his supervised independent living spot because he hasn’t been home in months, which will make him not compliant with the terms of his extended foster care.

His sisters Amanda and Ariana live together in a foster home. Amanda and Ariana are fiercely protective of one another, which has landed Amanda in jail. Another girl living in the foster home was mean to the quiet Ariana, so Amanda stepped in and things got out of control. When her caseworker and CASA visited Amanda in jail, she was embarrassed about what happened. She knew better. But now she’s seeing the consequences of her actions as an adult. Amanda and Ariana are supposed to attend orientation for Tarrant County College at the beginning of August. Judge Gonzales’ hands are tied until Amanda is released from jail. Things could be much worse for Amanda though. Her foster home is willing to let her come back. Her summer internship that was secured through the Texas Workforce Commission is allowing her to intern during the fall semester instead.

Ariana is doing well despite her siblings and core support system unavailable to her. She is excited about her new job at a nearby Pizza Hut. Ariana is quiet, she keeps to herself, and gets along with most in her foster home. She’s attending Tarrant County College (TCC) in the fall despite being recruited by Texas Women’s University to play basketball. Judge Gonzales, her caseworker and CASA have all encouraged her to follow her passion – basketball, but Ariana wants to be around her siblings. She wants to try TCC for a semester or two before making any decisions. Judge Gonzales connects her with the Texas Workforce Commission so she can have an opportunity that is unique to her – something her siblings don’t also have.

The statistics for youth aging out of foster care can paint a grim picture. According to the National Foster Youth Institute, of the thousands of youth who age out of the foster care system every year, 20% will find themselves homeless within the year. But Judge Gonzales refuses to give up on the youth in her charge. “If we keep planting the seed, it will sprout,” she says.

Each of the cases that Judge Gonzales oversees receive the same treatment. It’s mandatory for children and youth to attend court four times per year – once a quarter. In traditional family court, each case goes before a judge twice per year and children/youth don’t attend. But Judge Gonzales wants to see and hear from the children in her charge. She schedules her dockets around her busy days. It’s a point of pride that she doesn’t pass cases along to other judges.

Judge Delia Gonzales is not only improving the child welfare system as a whole through her work at the Permanency Court, but she’s changing the lives of the children in the system. She cares about each and every one. When appointed to the court, Judge Gonzales met with all the stakeholders and asked them, “What would the system look like in a perfect world?”

In 2023, The Rees-Jones Foundation was grateful to begin partnering with the Friends of Foster Kids organization tied to the Dallas County Child Protection and Permanency Court. Through the nonprofit, children and their families will now have even greater opportunities to receive necessary items Judge Gonzalez deems necessary for each child’s success. In the past, individual donors gave so that the court could provide for counseling appointments, new clothes, food gift cards, and more items so each child and their family never lacked what they needed to succeed together. Now, Friends of Foster Kids will have the ability to raise funds specifically so that when the court deems a child has needs that require a quick response, Judge Gonzalez will have eveerything needed at her disposal to bring hope to every child who steps into her courtroom.

*Names are changed for privacy.

[a]: https://nfyi.org/51-useful-aging-out-of-foster-care-statistics-social-race-media/

Share this post:

Category: Grant MakingOriginal ContentUncategorized

Power of Place-Based Investments Can Lead to Better Outcomes for Children By Trey Hill, Senior Program Officer…

Why Home Mentoring is Key to Child Abuse Prevention By Ona Foster, CEO of Family Compass [In…